From The Vault: Benny Goodman at Robin Hood Dell

MANN MUSIC ROOM: VAULT

Blog Entry by Jack McCarthy, Historian, The Mann Center for the Performing Arts

The Mann Center traces its history to the Robin Hood Dell, which opened in 1930 in East Fairmount Park as a summer home for The Philadelphia Orchestra. In 1976 the organization moved to a new venue in West Fairmount Park. Originally called Robin Hood Dell West, it was later renamed the Mann Music Center in honor of its longtime director and benefactor Frederic Mann, and subsequently renamed the Mann Center for the Performing Arts.

Jazz clarinetist and bandleader Benny Goodman’s debut at Robin Hood Dell in 1941 was notable for several reasons. One involved a dispute with a famous, temperamental conductor that made national headlines. Another was that the concert featured the world premiere of a new work by noted composer Igor Stravinsky, with Goodman himself leading the piece in his symphonic conducting debut. But perhaps most significantly, the concert was the first time a racially integrated group performed at the Dell, a fact that drew little notice in the mainstream press but represented an important milestone for the venue.

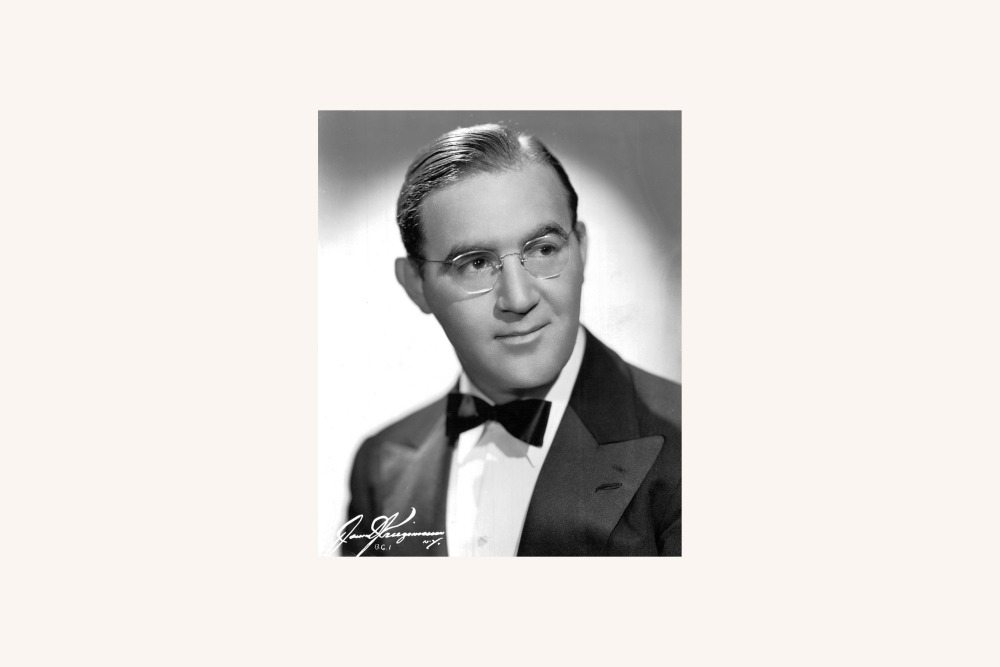

Born in Chicago in 1909, Benny Goodman rose to fame in the mid-1930s as the “King of Swing,” leading the nation’s most popular big band during the height of the Swing Era of jazz. While not a vocal civil rights activist, Goodman used his popularity to break down racial barriers of the time by featuring small integrated ensembles at his shows. Black and white jazz musicians sometimes played together informally or in small clubs in the 1930s, but societal norms did not allow integrated bands in major venues. Goodman was one of the first to successfully challenge such discrimination by having Black and white musicians play together in small groups as part of his big band shows. There were several iterations of Goodman’s small groups over the years, from trios to sextets. The most famous was the late 1930s quartet featuring Goodman on clarinet, Teddy Wilson on piano, Gene Krupa on drums, and Lionel Hampton on vibraphone. Goodman and Krupa were white; Wilson and Hampton were Black. Due to his enormous popularity, Goodman essentially forced major concert and dance halls to book his integrated small groups when they engaged his much in-demand big band.

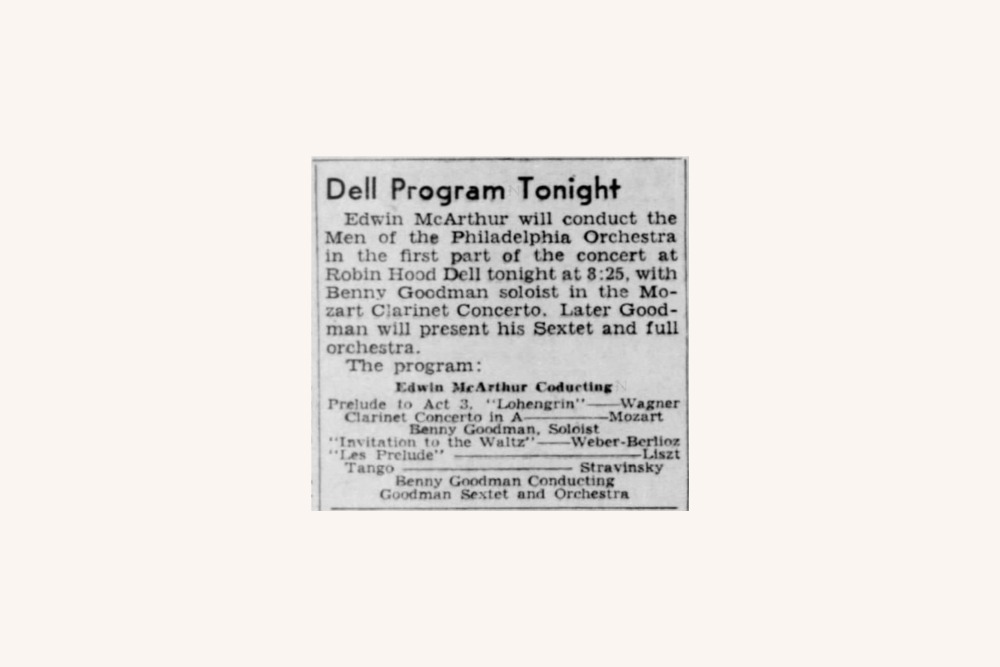

Goodman was still at the height of his fame when he was booked to play the Robin Hood Dell with his sextet and big band on July 10, 1941. An accomplished classical as well as jazz musician, Goodman did triple duty that evening: he was featured soloist in Wolfgang Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto; he conducted the world premiere of Tango, a short piece composed by Igor Stravinsky in 1940; and he performed with his sextet and big band. The conductor for the Mozart concerto and rest of the symphonic part of the program—including works by Wagner, Liszt, and Weber-Berlioz—was to be Spanish conductor/pianist Jose Iturbi, a world-renowned artist and frequent performer at the Dell in its early years. Iturbi was a mercurial personality and when he learned that Goodman was to be the soloist, he balked. "[Goodman] is a jazz-band leader. It would be beneath my dignity to conduct for him," he said, insisting that Dell management find another soloist. Upon hearing this, Goodman suggested that the Dell find an American conductor instead, which is exactly what they did, engaging conductor/pianist Edwin McArthur. The dispute made national headlines, reported in the New York Times, Time magazine, and other publications.

The Stravinsky piece, Tango, was the first work the great Russian-born composer wrote entirely in America. Having recently settled in Hollywood after leaving war-torn Europe, Stravinsky had lost much of the royalty income from his earlier works and reportedly wrote Tango to make money. The three-and-a-half-minute piece is rather conventional harmonically and rhythmically, especially by Stravinsky’s groundbreaking standards. Originally written for piano, the version Benny Goodman led in the piece’s premiere at the Dell was scored for chamber orchestra by Felix Guenther, a German-born pianist, arranger, and conductor who had also recently fled Europe. Stravinsky reportedly approved Guenther’s arrangement. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, while the rest of the program was very well-received, the Stravinsky piece as conducted by Goodman “earned a moderate reception from the audience. Presumably, it was the music.”

Following the classical selections, the final part of the program featured Goodman’s sextet and big band. The sextet at this time included Black musicians Cootie Williams on trumpet, Big Sid Catlett on drums, and Charlie Christian on guitar, and white musicians Mel Powell on piano, Walter Iooss on bass, and Goodman on clarinet. However, Christian, the great electric guitar innovator, became ill just before the engagement (he died of tuberculosis in early 1942) and was replaced by white guitarist Tom Morgan. Newspaper accounts indicate that both Catlett and Williams also played with the big band, which would have been yet another advancement in breaking racial barriers, as it was generally just Goodman’s small ensembles that were integrated at this time, not the full band.

African Americans had been featured at the Robin Hood Dell previously: the Hall Johnson Choir performed regularly in the early 1930s and singers Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson made their debuts at the venue in 1940. Robeson was actually featured soloist in a return engagement at the Dell the night before Goodman’s 1941 performance. These appearances by African Americans were in “separate” capacities, however, with the soloists situated in front of the orchestra or the ensemble performing in its own featured part of the program. It was not until Benny Goodman and his musicians took the stage on July 10, 1941 that Blacks and whites actually played together side-by-side at the Dell.

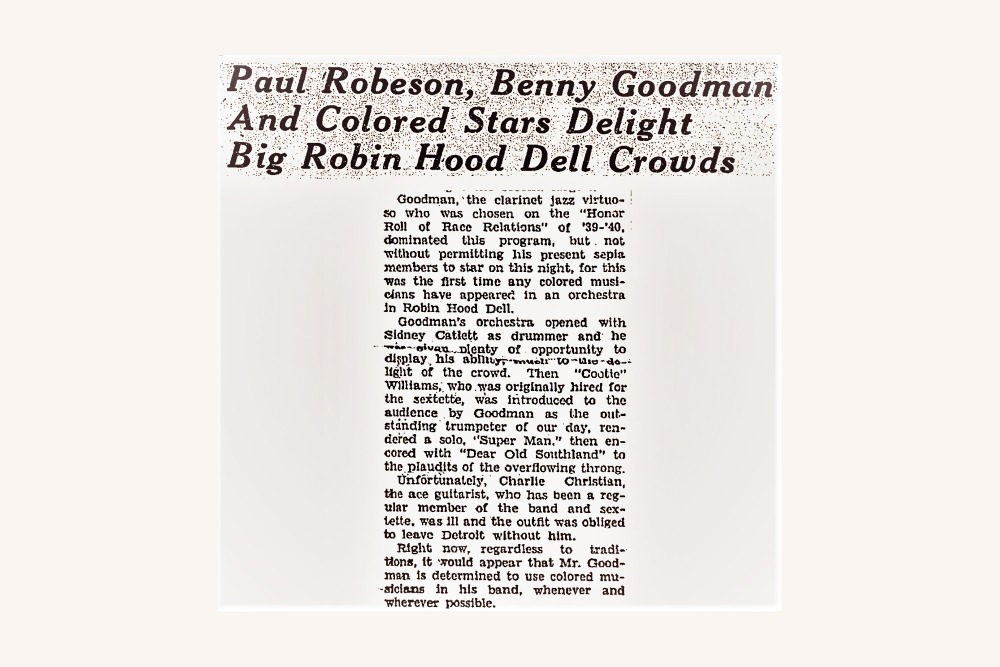

Most of the city’s mainstream press did not make note of this fact, but the Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s African American newspaper, did. In a July 17, 1941, review of the Paul Robeson and Benny Goodman concerts under the headline “Paul Robeson, Benny Goodman, and Colored Musicians Delight Big Robin Hood Dell Crowds,” the paper noted that the Goodman concert “was the first time any colored musicians have appeared in an orchestra at the Robin Hood Dell,” and that “regardless to traditions, it would appear that Mr. Goodman is determined to use colored musicians in his band, whenever and wherever possible.”

While largely forgotten today, the July 10, 1941 concert at Robin Hood Dell was another step in the breaking down of racial barriers in American music and a notable event in Philadelphia music history.