From The Vault: Hall Johnson Choir at Robin Hood Dell

MANN MUSIC ROOM: VAULT

Blog Entry by Jack McCarthy, Historian, The Mann Center for the Performing Arts

The Mann Center traces its history to the Robin Hood Dell, which opened in 1930 in East Fairmount Park as a summer home for The Philadelphia Orchestra. In 1976 the organization moved to a new venue in West Fairmount Park. Originally called Robin Hood Dell West, it was later renamed the Mann Music Center in honor of its longtime director and benefactor Frederic Mann, and subsequently renamed the Mann Center for the Performing Arts.

The Robin Hood Dell hosted a number of African American artists in its early years. Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Duke Ellington were among the noted Black performers featured at the Dell in its first two decades. However, the first African American group to perform at the Dell—and certainly one of the most popular, judging by the frequency of their appearances in the early years—was the Hall Johnson Choir, which performed every year from 1931 to 1934.

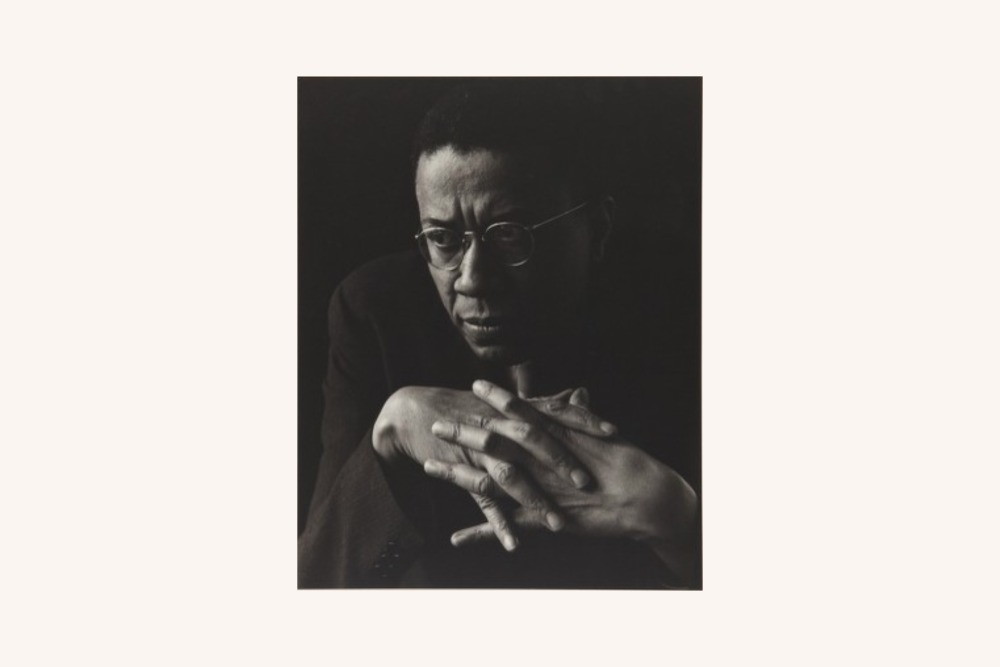

Composer and choral director Hall Johnson was born in Athens, Georgia, in 1888 into a musical family. He had formal musical training at home and at school, but was also deeply influenced by the music at the church of his father, a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal church, and by his grandmother, who had been born a slave and who sang Negro spirituals to him. After graduating college in the South, Johnson studied music theory and composition at the University of Pennsylvania from 1908 to 1910. Later, he studied at the University of Southern California and the Julliard School in New York City. In the mid-1910s, Johnson settled in New York and became part of the Harlem Renaissance, the early-twentieth century flourishing of African American literature, art, and civic life that was centered in Harlem.

The Hall Johnson Choir’s specialty was performing their leader’s arrangements of Negro spirituals. Negro spirituals were African American religious songs created in the pre-Civil War era by enslaved southern Blacks. Part of an oral folk tradition originally practiced exclusively by and for Blacks, spirituals were brought to broader public attention in the 1870s by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an African American choral group that toured and concertized extensively in the late nineteenth century to raise money for Fisk University. The group presented Negro spirituals in more polished form, transformed from improvisatory slave songs into formally arranged choral pieces. Johnson heard these arranged spirituals in his youth, but he also heard the songs in their original form as sung by his grandmother and others of her generation. He later noted that “the memory of those old-time singers and the songs they created became the most powerful single influence upon my life.”

Johnson established what later came to be known as the Hall Johnson Choir in 1925 in New York City. Within a few years they were performing regularly in concert and on Broadway and had developed an excellent reputation. They debuted at the Robin Hood Dell on July 24, 1931, a year after the venue opened. Following the usual format at that time for Dell concerts with guest artists, the first half of the program consisted of symphonic works, with the featured artist appearing after intermission. The conductor for the first half this night was Eugene Ormandy, then five years away from being appointed conductor of The Philadelphia Orchestra. Ormandy opened the program with two pieces by Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, the second of which—Symphony No. 9, “From the New World”—was no doubt chosen intentionally for the occasion. Dvorak wrote the symphony while in the United States serving as director of the National Conservatory of Music of America in the 1890s, during which time he championed Negro spirituals as the basis for an American school of composition. “I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies,” Dvorak said, “They are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.”

Hall Johnson did just that, using the Negro spirituals that had made such an impression on him in his youth as the basis for sophisticated choral arrangements he wrote for his choir. The ensemble varied in size, but usually had twenty- to thirty-some singers, all African American. Reflecting in later life on the choir’s founding, Hall wrote that the “principal aim was not entertainment. We wanted to show how the American Negro slaves … created, propagated, and illuminated an art-form, which was, and still is, unique in the world of music.”

The Hall Johnson Choir’s 1931 debut at the Robin Hood Dell consisted of a pair of concerts on July 24 and 25. Their program each night was comprised of eight songs, broken into three groups of two or three songs each, all arranged by Johnson. Included were well-known spirituals such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Go Down Moses,” and “Steal Away to Jesus.” They also sang a blues song, “St. James Infirmary.” While spirituals comprised the group’s main repertoire, they occasionally performed some blues and work songs, which were part of the broader African American vocal tradition that gave rise to the spiritual. Audience response was very enthusiastic, and they were invited back for four straight years.

Philadelphia music critics also loved them. Reporting on the second of the two concerts in 1931, the Inquirer wrote, “The Hall Johnson Negro Choir scored another tremendous success at … the Robin Hood Dell last night, presenting a totally different programme [sic] from that which marked the debut … of these remarkable singers the previous night. As before, they displayed striking range in vocal resources and diversity of numbers, winning prolonged applause.” The same reviewer, reporting four years later on the group’s 1934 appearance, wrote, “Vociferous applause and shouted requests for encores greeted the Hall Johnson Negro Choir at Robin Hood Dell last night … The same qualities of sincerity, conviction, and artful unanimity of effort which have earned unique distinction for the Hall Johnson Choir in the past marked the singing of all the numbers heard last night.”

The group did not perform again at the Dell until 1938, probably because Johnson spent a good part of the latter 1930s and early 1940s in Hollywood, where he and his choir appeared in several movies. They were scheduled to return to the Dell for two concerts in late July 1938, but both shows were rained out and rescheduled into a single concert on August 1, 1938. Hall Johnson himself could not make the new date, however, so a substitute conductor led the group. As before, critical reviews were very positive. The Inquirer noted that “Those qualities of fervor and feeling, plus finish, which distinguish the singing of the Hall Johnson Choir, marked the full-throated presentation of the songs on the program.” This was the final appearance of the Hall Johnson Choir at the Robin Hood Dell.

When Hall Johnson died in 1970, the great contralto Marian Anderson, who had worked closely with him and recorded a number of his vocal arrangements said, "Hall Johnson was a unique genius. For although he invented no new harmonies, designed no new forms, originated no new melodic styles, discovered no new rhythmic principles, he was yet able to fashion a whole new world of music in his own image."