From the Vault: Duke Ellington First Concert with Symphony Orchestra (1949)

MANN MUSIC ROOM: VAULT

Blog Entry by Jack McCarthy, Historian, The Mann Center for the Performing Arts

The Mann Center traces its history to the Robin Hood Dell, which opened in 1930 in East Fairmount Park as a summer home for The Philadelphia Orchestra. In 1976 the organization moved to a new venue in West Fairmount Park. Originally called Robin Hood Dell West, it was later renamed the Mann Music Center in honor of its longtime director and benefactor Frederic Mann, and subsequently renamed the Mann Center for the Performing Arts.

Duke Ellington was one of the greatest bandleaders and composers in the history of jazz. Under his direction, the Duke Ellington Orchestra was continually at the forefront of innovation and experimentation in jazz and big band music. Ellington’s first pairing of his band with a symphony orchestra took place at the Robin Hood Dell in July 1949.

Born in 1899, Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington took over leadership of the ensemble that would become the Duke Ellington Orchestra in the early 1920s and quickly established himself as an important bandleader and composer. While working within the traditional big band format, in the 1940s Ellington began writing longer-form works that were a major departure from the dance tunes and romantic ballads that comprised the repertoire of most big bands of the time. Ellington’s engagement at the Robin Hood Dell on July 25, 1949 gave him the opportunity to try a new innovation of combining the forces of his seventeen-piece band with those of the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra.*

*Many sources state that Ellington’s band played with The Philadelphia Orchestra that night, which is not technically accurate. A few years after the Robin Hood Dell opened in 1930, the name of the resident ensemble was changed from The Philadelphia Orchestra to the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra. While the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra was comprised primarily of Philadelphia Orchestra musicians, it did not include the latter’s key first chair players and was not under the artistic control of its music director.

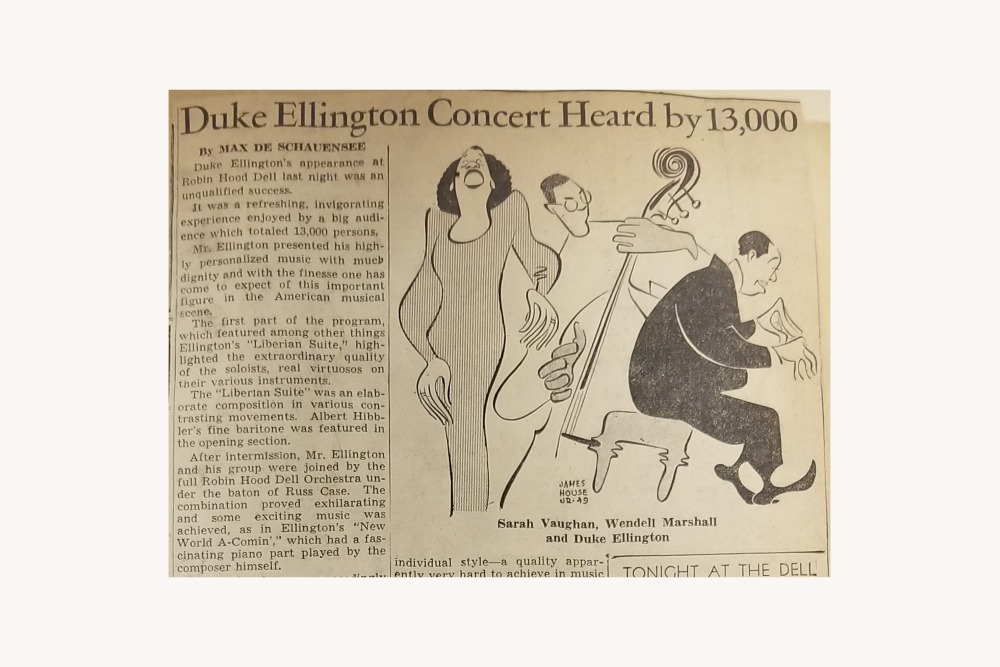

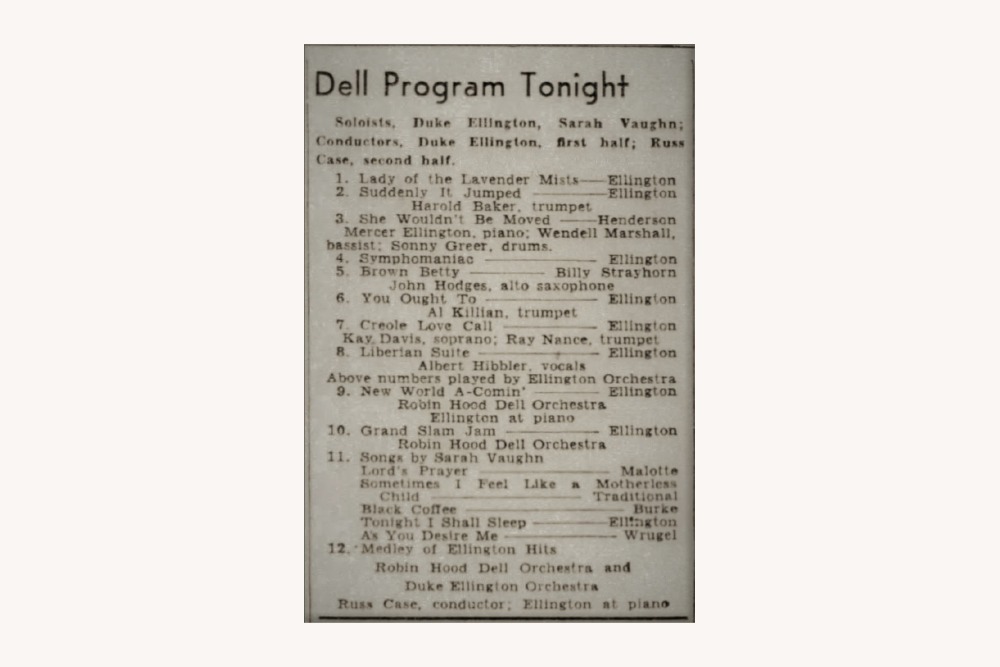

The first half of the program featured just the Duke Ellington Orchestra, with Ellington in the triple role of bandleader, pianist, and composer. The band played all Ellington tunes, along with a song by his long-time writing partner Billy Strayhorn, with featured solo turns by the band’s noted instrumentalists and vocalists. They also played a longer-form piece entitled “Liberian Suite,” which the Liberian government commissioned Ellington to write in 1947 in honor of the centennial of the African nation’s independence.

It was in the second half of the program that the Ellington and Robin Hood Dell orchestras combined forces and presented their version of “symphonic jazz.” Russ Case, an experienced conductor and arranger, directed the merged ensemble—around 117 musicians—in the performance of two Ellington compositions: “New World a Coming” and “Grand Slam Jam.” “New World a Coming” was a rhapsodic piece for piano and orchestra, with the composer at the piano. Duke had premiered the piece at Carnegie Hall in 1943, but just with his band, not with a symphony orchestra as now performed at the Robin Hood Dell. “Grand Slam Jam,” an adaptation of a riff-based tune on which the Ellington band would sometimes jam, was written specifically for the Robin Hood Dell concert. As such, it is Ellington’s first composition for band and symphony orchestra. Duke was so pleased with how well the two ensembles integrated on “Grand Slam Jam” that he later refashioned the piece and recorded under the new title, “Non-Violent Integration.”

Also on the bill for the July 25th concert was singer Sarah Vaughan, then a rising star who would soon become one of the premiere vocalists in jazz. Following the combined orchestra performance, Vaughan sang several songs and, according to some reviewers, nearly stole the show. When Vaughan was finished, the two orchestras combined again for a finale of a medley of Duke Ellington’s hits, with Russ Case again conducting and Ellington at the piano.

The concert was an important milestone for Ellington—he mentions it in his 1973 autobiography, Music is My Mistress—and the event was covered by both local and out-of-town newspapers, including several African American newspapers. Among the latter was the following enthusiastic review by the Pittsburgh Courier, which also mentions Frederic Mann, who was in his first season as president and manager of the Robin Hood Dell:

Duke Ellington and Sarah Vaughan enjoyed their finest hours here last Monday night when they became the first beige artists of their ilk to starline [a] … Robin Hood Dell Fairmount Park concert … Something to look forward to on the part of serious-minded music lovers, the Dell has nonetheless never slighted talents of the race. In the past such greats as Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Hazel Scott Powell have spiced the evenings with their great ability. This, however, is the first time that its president, the very personable Frederic R. Mann, has dared to mix the popular colored talent with those who adhere to the compositions of the masters.

For real Americans, and there were 13,000 of them niched into the amphitheatre created by nature in a sloping dell in Fairmount Park, it was one of those rare thrills. A star-spangled montage of fine American democracy waving its talent in the breeze to strike the ears and stir the imagination of a humanity that was on this night woven into one because of a one and the same love for music.